Yağmur Dikener, 2021

|

| New Planet, Konstantin Yuon - 1921 |

The Soviet art has been a phenomenon that has been discussed and respected all over the globe where a majority of its artists are still recognised to be the prominent forerunners of the art today. Yet, the Soviet-era art does not necessarily connotate to the stereotypical idea of works of propaganda illustrating healthy, lively, colourful figures achieving great successes or living through their synthetic perfect lives. Instead the Soviet art can be marked by different periods, where art finds form in various ways according to the qualities of the Soviet leaders. Within such, our contextualisation of stereotypical Soviet images resides with especially the Stalinist era with increasing pressure on symbolic and cubic art; and an increasing support directed towards the ‘Soviet realism’. Yet to be able to present a realistic image of what Soviet art really is, it is a must to understand the complete picture including the forerunners in the early years of post-revolution whom have been strapped of their artistic title several decades later from being the commissioners of arts and heads of universities in the newly established Soviet Union. The following essay will try to grasp the prioritised artistic ideas prevailing through the early periods of Soviet Union, paying specific focus on some of the most preeminent artists.

Since

art is an organic phenomenon, it is not possible to strap it from its natural

flow and timeline. In other words, to understand the early Soviet art in the

post-revolution period, the first phenomenon that must be understood is

pre-revolution Russian art scene where the artists we know as great Soviet

artists were growing into their artistic styles.

To being with, the pre-revolution era art scene can be marked with two distinct spheres: one being the leftist artists mainly producing Avant-garde, futuristic, abstract expressionist works, and the other being traditional artists grouped in several associations such as the Revolutionary Russian Artists Union.

In the pre-revolution years, especially in the 1910s, the Russian art scene was marked by the Russian Avant-garde, the Miriskusstva, where Benois and other significant artists claimed that the industrial society was not aesthetic, thus the arts must resemble the Romantics, the folklore, and the 18th century Rococo. With such, this brand of artists believed that their purpose was to save the world by beauty. What is ironic is that, nearly a decade later a direct opposite idea prevailed in Russia where the fascination with the industrial society is included in every element of the majority of art produced.

A prominent group in

Russian Avant-grade were the Blue Rose Group which swept the art scene between 1906

to 1908 whom utilised colour as a tonal medium to create rhythm. What is

especially significant about them was a member, Wassily Kandinsky whom had a

name for himself both in the European and Russian art scene.

Another

significant art wave under leftist Russian sphere was futurism which accepted

Filippo Marinetti’s futurist manifesto where the past was deliberately

rejected, and elements such as speed, machinery, violence, youth, industry,

modernisation and cultural rejuvenation were celebrated. The Russian futurism prevailed

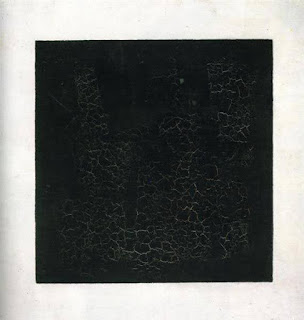

with the works of Kazimir Malevich. Malevich, an artist we might know from his

famous paintings of squares and rectangular shapes, believed that the arts have

surpassed the need to reflect plain nature or forms of it. For him, it was

impossible to capture the beauty of nature and artists are doomed to fail in

such path, as nature constantly changed in form. Rather he believed that the

artists must be in constant movement with the world and its discoveries since

it was irrational to ignore the advancements in science and technology. Instead

of ignorance, artists were rather to take active part in it. This viewpoint can

be illustrated in one of his most famous work and the first recognised painting

of Supremativism, ‘the black square’ or ‘the black cube’; which consists of a

black square shape covering the majority of a white space. Although from afar

the painting can be judged to be too simplistic, its significance lays in both

its meaning and its place in the historical timeline of visual arts. For many

of the art historians, this work marked the point zero of painting; where the

idea for such painting is though to be arisen from the décor of Matyushin’s

opera of ‘Victory Over the Sun’. Simply, this work showed individual’s active

creative power in its passive form, reigning its victory over nature. Hence, in

this painting, what emerged instead of a solar circle, was instead a square.

|

| The Black Square, 1915, Kazimir Malevich |

In the post-revolution

period, Malevich stood as one of the forerunners for the Soviet art; taking

part in many of the art scenes such as cubism. Yet, with Lenin’s death and

Stalin coming to power, a major shift, very much similar to that of a paradigm

shift, occurred; which cost Malevich many of his works and his academic

position, with his art being confiscated and any future artwork being prevented

by prohibitions. He was even jailed during this period in 1930 due to

suspicions raised by his visits to Poland and Germany.

Returning

to our original path in pre-revolution Russian art, it can be said that

Supremativism created under the leadership of Malevich consisted of many

artists whom produced not only two-dimensional, but also three dimensional

artworks. With the sole purpose of achieving beauty rather than practicality or

usefulness, designs for tea sets, dishwashers and even skyscraper plans were

produced. What was especially significant about Supremativism was about it

coexisting with the art wave directly opposed to it, the Constructivism which

focused on pure functionality. To express in material terms, if a dishwasher

was to produced under Constructivism it was to be used, and if a building were

to be designed it must be suitable for work and leisure.

|

Suprematist tea set. Designed in 1918, Kazimir Malevich |

Moving on to the

Abstract Expressionists, Kandinsky, a figure mentioned above under the Blue Rose

Group reappears. Before his return to Russia in 1914, he founded the school

‘Phalange’ in Germany and greatly contributed to the European art scene. After

his return, he emerged as one of the most prominent artists in terms of shaping

the post-revolution art scene, with his efforts in founding the Soviet Art

Culture museum under Lucharsky even though he left Soviet Union after a period

of three years due to his spiritual position being alienated in the polemical

materialism in Soviet society. By contextualising the Avant-garde atmosphere

prevailing in Moscow, his works of demi-abstractionist, impressionist

landscapes and romantic fantasies were said to be influenced from such art

scene. In his technique and style, he focused on the geometric abstraction of

individual elements, or in other words simplification. Likewise to supremativists, Kandinsky stood in opposition to the constructivists whom were

critical of his art. Punin’s remark of ‘mutilated spiritism’ as a depiction of

Kandinsky’s work were only one of such critics. Thus, his works were also under

the attack of Stalinism and Soviet realism after a decade later, where the

artworks were prohibited from being displayed in museums. Yet, after leaving

for Europe in 1920 and later participating in the Bauhaus school and the Geralt

principles; he became the Kandinsky he is today.

|

| On white II, 1923, Wassily Kandinsky |

Another significant wave that prevailed both in the pre-revolution and the post-revolution period was constructivism, an artistic and architectural philosophy that was brought about by Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko in 1915. This philosophy’s purpose was to depict and reflect the modern industrial society and urban area. It refused movement and aesthetical stylisation in favour of industrial materials. For Constructivism, the art was to serve practical and social purposes. Perhaps, the most famous of the Constructivist works is the ‘Tatlin tower’, a work which stands as the inspiration of many others today, one being the Georges Pompidou Centre in France. Tatlin’s tower was originally designed to be Cominterm’s, the Third International, headquarters and monument, and planned to be located in Petrograd, or with its current name Saint Petersburg. Yet, this architectural plan only stood as a sample, since even if that much lead was to be found; within the economic conditions, the housing crisis and the political turmoil of the newly established Soviet state, it would still be impossible to build the Tatlin’s tower. However, even if it was an impossible design in terms of resources, its significance stood in the essence of its design, the practicality and the symbolic nature. The purpose was to supersede Eiffel’s modernism. Hence, it was deemed by Shklovsky as “made from iron, glass and revolution”.

|

| Tatlin's Tower, or the project for the Monument to the Third International, 1919-1920, Vladimir Tatlin |

In the immediate art

scene in the aftermath of 1917 Revolution, it is possible to recall three

artists as forming the theoretical basis for the leftist art school: David

Shterenberg, Aleksandr Drevin, and Wassily Kandinsky under InkHunk. Yet for the

sake of context, only the association of InkHuk, the Institute of Artistic

Culture, will be analysed since all three figures took part in such

organisation. With the first director Kandinsky, the InkHuk was found in 1920

and remained active until 1924. For Shterenberg, who was the director of IZO at

the time, InkHuk had the purpose of “determination of scientific hypotheses on

matters of art”, where the area of research included three areas: research

regarding the main elements in painting, sculpture, architecture, music and

dance; the way different arts were connected by internal, organic and synthetic

ways; and finally the Monumental Art which Kandinsky saw as the future of the

art scene.

|

| In Grey, 1919, Wassily Kandinsky |

To summarise the leftist

view in pre-revolution art scene and the early Soviet era, Nikolai Punin’s

words can be utilised. “If the depiction of the world does aid cognition, then

only at the very earliest stages of human development, after which it already

becomes either a direct hindrance to the growth of art or a class-based

interpretation of it. The element of depiction is already an element

characteristic of a bourgeois understanding of art.”

On the other hand, the

second great sphere marking early Soviet art were the traditional artists whom

continued their realistic depictions of life and figures. Later by transforming

into Soviet realism, the paintings done by artists of the traditional sphere

mark the classical and popular imagery we know from the revolutionary era and

the Soviet Union. One of such artists was Isaak Brodsky, a student of Repin,

whom was a member of Revolutionary Russian Artists Union, whom we might know

from the very famous depictions of Lenin whether it be him sitting in a room

scribbling notes, or giving speeches to the masses. By depicting historical

events such as the shooting of 26 Baku commissars, images of Stalin and

landscapes: Brodsky became on the most known Russian artists.

|

| Speech by Lenin before the Red Army, sent to Polish front May 5, 1920, Isaak Brodsky |

Another significant

artist was Boris Ioganson, whom painted works that are recognised to be one of

the best examples of socialist realism. This was due to his creation of moral

values of good and bad that can be grasped in seconds by just one stare at the

figures. The works stood as symbols for heroic myths of the psychological

battle between the proletariat and the ‘owner’.

Hence, his paintings focused on the duality of classes and their

encounters. Even if one class resided within the painting, their opposition was

without doubt since the moral nature of his figures resided in their class

relations. Such can be understood from his painting of ‘Conspiracy of the

Kulaks’ dating back to 1933, 1934. With the Stalinist era and the new paradigm

shift in arts, he was an increasingly celebrated artist; thus even in the

de-Stalinisation period his works continued to be masterpieces. Within such,

in-between 1958-1962 he served as the head of USSR Arts Academy, and in-between

1965-1968 he served as the head of USSR Union of Artists.

|

| Conspiracy of Kulaks, 1933-34, Boris Ioganson |

A third and final artist

can be recalled for understanding, although not a full one, the traditional

artists whom are later to become the remarkable figures of socialist realism, a

‘nationally’ endorsed style of visual arts: Aleksandr Deineka, a painter of the

belief in revolution and Soviet power which embarked a similarity between a

poet friend of his, Mayakovsky whom also showed endorsement and love for the

proletariat, and excitement towards physical strength and health. Thus, comes

about the painting ‘Left March’ of Aleksandr Deineka inspired by Mayakovsky’s

poem with the same name.

|

| Left March, 1941, Alexander Deineka |

What was so significant

about Deineka was especially how his art styles transformed over the years

including the ‘sniper art’ he painted which consisted of a very

charachteristical use of color and movement illustrated in the dynamics of the

proletariat; the scenes from warfare from his visit to Sivastopol in 1941, the

famous mosaics at Mayakovskaya metro station, images of happy and healthy

fisherwomen, depictions of sports and health, and finally imagery of Soviet

successes.

|

| Mosaic on the Mayakovskaya Metro Station, 1938. Detail. Aleksandr Deineka |

|

| At the construction site of new workshops, 1926, Aleksandr Deineka |

In the later years, the early voices of traditionalists transformed into the depictions of Soviet power and beauty under socialist realism, casting aside the abstract and expressionist nature held by the competing leftist sphere. Yet, what can be said is that both spheres left great remedies in the art scene and can be celebrated today as depictions of form and story.

Yorumlar

Yorum Gönder